History of the House

Contents

Timeline

The Dolman Family and Shaw House

The House that Thomas Dolman Built

A Family Divided

Sir Thomas Dolman

The Last of the Dolmans

Royal Visitors

Discover Shaw: The Exterior

Shaw Under Siege

Discover Shaw: The Ground Floor

A Dukes Country Retreat

Discover Shaw: The First Floor

A Georgian Country Estate

Notebooks

A Social Reformer at Shaw

The Last of the Andrews Family

A Victorian Family Home

The Twentieth Century

Community Disputes

Life at Shaw House between the Wars

The Second World War

Shaw House School

The Decorative Scheme

Timeline of Ownership

| 1554 | Thomas Dolman (c.1510-75) |

|---|---|

| 1575 | Thomas Dolman II (1542/3-1622) (legal title from 1577) |

| 1581 | Shaw House was built |

| 1622 | Humphrey Dolman (1593-1666) |

| 1666 | Sir Thomas Dolman III (1631-97) |

| 1697 | Sir Thomas Dolman IV (1657-1711) |

| 1711 | Dorothy Dolman (m. John Talbot) (d. 1724) |

| 1724 | Lewis Dolman Talbot (b. 1720) |

| 1728 | James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos (1673-1744) |

| 1744 | Henry, 2nd Duke of Chandos |

| 1751 | Joseph Andrews (1692-1753) |

| 1753 | Sir Joseph Andrews II (126-1800) |

| 1800 | Sir Joseph Andrews III (1768-1822) |

| 1822 | Elizabeth Hunt (nee Andrews) (1771-1822) |

| 1822 | Rev. Dr. Thomas Penrose (1770-1851) |

| 1851 | Henry Richard Eyre (1813-76) |

| 1876 | Henry John Eyre (1854-1917) |

| 1905 | Kathleen Farquhar (1850-1935) |

| 1935 | Sir Peter Farquhar (1904-86) |

| 1939 | Requisitioned for military use during the War |

| 1943 | Taken over as temporary school premises by Newbury Council Schools |

| 1945 | St Gabriel’s School (remained in use by Council School) |

| 1949 | Berkshire County Council |

| 1998 | West Berkshire District Council |

| 2003 | Restoration of Shaw House began |

| 2006 | Shaw House opened to the public. |

The Dolman Family and Shaw House

The story of Shaw House begins with the Dolman family, and their ambitions to move from industry into the realms of the landed gentry. They are thought to have originally come from Pocklington in Yorkshire, settling in Newbury in the 15th century. Here their fortune was made in the cloth industry, a highly prosperous profession of the period. Thomas Dolman was keen to establish his family’s position within the landed classes both by purchasing property and building a new house to show off his status. This move into property and land was well-timed as it coincided with the beginning of a decline in the cloth industry in England. Contemporary documents refer to the clothiers of Newbury retiring to their country estates “causing persons to live idly” 1

In 1554 Dolman bought the manor house at Shaw and most of its land2 from the Crown for the sum of £600. When he died in 1575 the manors of Shaw and Speen were left to his second son, also called Thomas. His eldest son, John had already received a manor to the north-west of Newbury at the time of his marriage, but he successfully contested the will and consequently acquired Shaw. However, in 1577 Thomas Dolman II bought out the rights to Shaw from his elder brother and within four years he had completed his new manor house at Shaw.

The House That Thomas Dolman Built

Thomas Dolman II (1543-1622) was thirty-five when he inherited the Manor of Shaw. At this time, the grandest houses were built by royalty, aristocrats and great statesmen, but not far behind them was a new class of successful self-made men who demonstrated their wealth, power and new status by building houses such as Shaw. Thomas Dolman’s education at Oxford University and the Inns of Court in London would have made him familiar with the latest trend in architecture that feature in the design of Shaw House. He also showed off his intellect in the inscriptions in both Greek and Latin on the south entrance porch. These translate as “Let no envious man enter” and “The toothless man envies the teeth of those who eat and the mole despises the eyes of the stag”. The inscriptions show that Dolman was well aware of the jealousy his new house would cause.

Thomas Dolman II (1543-1622) was thirty-five when he inherited the Manor of Shaw. At this time, the grandest houses were built by royalty, aristocrats and great statesmen, but not far behind them was a new class of successful self-made men who demonstrated their wealth, power and new status by building houses such as Shaw. Thomas Dolman’s education at Oxford University and the Inns of Court in London would have made him familiar with the latest trend in architecture that feature in the design of Shaw House. He also showed off his intellect in the inscriptions in both Greek and Latin on the south entrance porch. These translate as “Let no envious man enter” and “The toothless man envies the teeth of those who eat and the mole despises the eyes of the stag”. The inscriptions show that Dolman was well aware of the jealousy his new house would cause.

1 State Papers Domestic, Eliz. Xxxiiv,43

2 1145 acres 3 rods and 7 perches

The gentleman lived to enjoy his house for over forty years, dying at the great age of eighty on 22nd January 1622. Seven days after his death an Inventory for Probate was made by five local men who carefully recorded all of Dolman’s possessions in Shaw House. This document gives us a good idea of how the house was used in its early years. Thomas Dolman’s “qwne lodginge chamber” and its associated “little chamber within the said chamber called the maides chamber” and his “closet” are thought to have been in what is now known as The Oak Room. As well as Dolman’s rooms there are two other similar suites of rooms recorded in the Inventory suggesting that the principal members of the family each had their own private ‘apartment’. The furnishings for the Hall in the Inventory suggest its status as the most important room in the house had declined by this time. The description of furnishings in the Parlour 3 indicates that this was instead used by the principal members of the household both to dine and entertain guests in more intimate surroundings than the Hall. As well as tables and numerous chairs the furnishings included a pair of virginals4 , window cushions covered in gold taffeta, tapestries and paintings on the walls, and brass andirons5 in the fireplace to give the impression of ostentatious comfort. This room was on the ground floor at the south end of the east wing, its large windows providing excellent views over the gardens to the east of the house and the forecourt to the south. At the other end of this wing beyond the foot of the stairs was the study where Thomas Dolman kept his valuable collection of books. As well as recording the main rooms of the house the Inventory records all the contents of the service rooms. These details give a fascinating insight into all aspects of daily life at Shaw at this time from the cooking utensils in the kitchen to the value of the animal feed stored in the barns.

3 Rooms of this type were often known as the Great Chamber at this time

4 An early keyboard instrument similar to a harpsichord, often as at Shaw without legs and placed on a frame

5 Metal stands used to hold logs in a fireplace

A Family Divided

Humphrey Dolman inherited Shaw House in 1622, at the age of 29. Educated at Oxford and Lincoln’s Inn like his father before him, it must have appeared that life at Shaw would continue in peaceful prosperity for the foreseeable future. However, in May

Humphrey Dolman inherited Shaw House in 1622, at the age of 29. Educated at Oxford and Lincoln’s Inn like his father before him, it must have appeared that life at Shaw would continue in peaceful prosperity for the foreseeable future. However, in May

1641 the differences that had developed between Charles I and his opponents in Parliament surfaced at Shaw House. Humphrey Dolman refused to sign the Protestation against Popery, thus openly declaring himself as a Parliamentarian. The protestation was a declaration of loyalty to the King as well as an oath to preserve the status quo in Parliament and defend the Church of England against Catholicism. In contrast, Humphrey’s son Thomas, then aged twenty, took the oath and was to prove himself a staunch supporter of Charles I in the events that overtook Shaw House in October 1644 when the house served as the King’s Headquarters. Father and son became divided in their political allegiance.

It is not known what happened to Humphrey Dolman during the 2nd Battle of Newbury, but the eventual defeat of the King in 1645 led to a reversal of fortunes within the Dolman family. By 1647 Humphrey was nominated as a member of the Parliamentary Committee of Berkshire, whereas Thomas Dolman’s assets were confiscated by the Parliamentary Commissioners. However, following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 Humphrey’s name no longer appeared on any official documents. But this was not necessarily a reaction to his former political loyalties; he may have simply been in poor health. Humphrey Dolman died shortly after his will was dictated on 13th May 1666 in the presence of his doctors as he lay on

his bed “in an upper room (being his usual lodging and chamber) of his dwelling house in Shaw” 6 He left “all his estate whatsoever both within door and without” to his son, now Sir Thomas Dolman.

6 BRO D/A1/63/32a

Sir Thomas Dolman

Sir Thomas Dolman’s defiance of his father’s political stance was rewarded in February 1661 when he was knighted following the Restoration of the Monarchy. In the same year he became MP for Reading and was appointed a Justice of the Peace. His will states that “my first funeral to be in no ways expensive but in a private manner” and in general the document suggests that Sir Thomas had spent much of the Dolman fortune by the time of his death in 1697.

The Last of the Dolmans

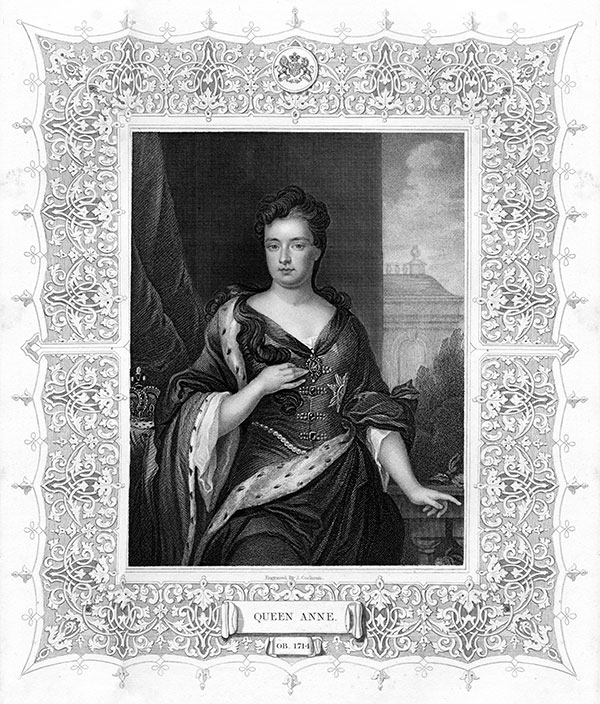

The second son of Sir Thomas Dolman, another Thomas became heir to the estate after his father’s death. Thomas was knighted in November 1703 following the Visit to Shaw House by Queen Anne on her journey from Bath to London. His appointment as Deputy Lieutenant of Berkshire and MP for Re

ading in 1705 suggest that Shaw remained his primary residence although he also had houses in London and Essex. Sir Thomas continued the renovation of the house and grounds that was probably started by his father; it would undoubtedly have been completed in time for Queen Anne’s visit to Shaw in 1703. All the work achieved at this time reflects the latest fashions in architectural and garden design. The last Dolmans brought Shaw House up to date with the intention of impressing royal visitors just as their ancestors had done over a century before. There were no surviving children from Sir Thomas’ marriage to Dorothy Bell, and his six siblings died before him.

From 1720, the Dolman family entered into lengthy negotiations with the Duke of Chandos for the sale of Shaw House. It eventually passed to him in 1728.

Royal Visitors

One ambition on completing a grand house in the seventeenth century was that your fashionable new residence might be favoured a stop by the Court on a Royal Progress. In this respect the Dolmans succeeded where many of their contemporaries failed. James I and Queen Anne visited Newbury in 1603 when the King granted the Manor of Newbury to his Queen. It seems likely that they would have stayed at Shaw on this occasion and been feted with a grand banquet in the great hall to celebrate. Queen Anne was to visit Shaw again on 4th September 1612, Robert Cecil stayed at Shaw on his hurried journey to Bath where he travelled in the hope of a cure shortly before his death. Over the following century Shaw was visited by almost every Stuart monarch, notably King Charles I (see Shaw under Siege). His sons followed years later in September 1663. “The Intelligencer” reported the visit to Shaw of King Charles II and James, Duke of York:

One ambition on completing a grand house in the seventeenth century was that your fashionable new residence might be favoured a stop by the Court on a Royal Progress. In this respect the Dolmans succeeded where many of their contemporaries failed. James I and Queen Anne visited Newbury in 1603 when the King granted the Manor of Newbury to his Queen. It seems likely that they would have stayed at Shaw on this occasion and been feted with a grand banquet in the great hall to celebrate. Queen Anne was to visit Shaw again on 4th September 1612, Robert Cecil stayed at Shaw on his hurried journey to Bath where he travelled in the hope of a cure shortly before his death. Over the following century Shaw was visited by almost every Stuart monarch, notably King Charles I (see Shaw under Siege). His sons followed years later in September 1663. “The Intelligencer” reported the visit to Shaw of King Charles II and James, Duke of York:

Thursday, August 27th. That night their majesties lodged at Sir Thomas Dolman’s house (about a mile from Newbury) where they were entertained together with Their Royal Highnesses (and indeed the whole court)with a magnificence. Prudence, modesty and order, to admiration.

The later reigning Queen Anne visited Shaw in 1703, and enjoyed the entire suite of rooms on the first floor that had probably been specially developed for her royal visit. Regardless of this exceptional treatment, she only stayed for two days! Nevertheless, the Dolmans had certainly come a long way from their humble origins in Yorkshire.

Discover Shaw: The Exterior

It is hard now to appreciate the impact that Shaw House would have made when it was first built. It dominated the road which passes the front of the house as well as being clearly visible from the major routes that passed through Newbury. The soaring gables, clusters of tall chimneys and narrow central stone entrance porch emphasised its height, and generated an effect which would have amazed the people of Newbury.

The date 1581 carved in Roman numerals (MDLXXXI) on the south porch and on a rainwater head on the east front records the year that the main structure of the house was completed. This is supported by the dendrochronology analysis (tree-ring dating) of roof timbers which established that they were from local trees felled in 1579 and 1580 to provide green oak for immediate use7.

The main walls of the house were constructed from locally made bricks that probably originated from a number of small brickworks. The sites of former local brick kilns are still recalled in the names of places such as Clay Hill and Brick Kiln Wood near the area of Shaw. The stone used for the plinth on the south porch was from Headington, Oxfordshire, and Bath stone was used on all of the upper stonework.

7 Oxford Dendrochronology, 2003

The H-plan of Dolman’s new house with two wings separated by a central range was a popular design towards the end of the 16th century. However, as originally built, Shaw was one of the earliest houses to have completely symmetrical façade in which the windows gave no hint of the interior layout. In 1581 the ground floor windows to the east of the south entrance porch matched the windows to the west of the porch making the exterior of the entrance front symmetrical. Re-worked brickwork has been discovered which suggests that changes were made to the sill levels around 1700. When constructed the plan of the north front of the house virtually mirrored the south front. The north porch is now concealed by the Loggia and first floor corridor, which were 19th century additions made by the Eyre family.

The west façade is the least altered elevation of the house. The windows here are generally as they were built and some retain the Elizabethan diamond-leads and original glass. The west doorway is the only original entrance door to the house. The survival of this façade may be due to the fact that it faced onto the stable yards and it was consequently considered unnecessary to change it in later centuries.

In September 1729 the Duke of Chandos asked his agent Mr Hall to get an estimate for “handsome large sashes of glass and woodwork”8 to replace the mullion windows on the front of the house which leaked9. As a result, sash windows were fitted to the dining room and the Duke’s dressing room, significantly altering the exterior of the house. The initials JH high up on the north front leave a lasting reminder of the Newbury builder Jonathon Hicks who was engaged by the Duke of Chandos to renovate the house in 1729.

Joseph Andrews’ death within two years of buying Shaw may have saved the house from being significantly altered in the 18th century. In 1750 he carefully drew up ideas for potential improvements. Of particular interest are a set of drawings he made for a radical modernisation of the south elevation10. he appears to have considered demolishing the wings of the house and replacing them with low pavilions which were to frame a classical front. Other drawings are for a relatively small classical villa. His son, Sir Joseph Andrews was the first owner of Shaw to leave any record of his ownership upon the exterior fabric of the house. High up on the west front above the doorway can be seen the fire mark of the Royal Exchange insurance company; a lead plaque numbered 34640. The company accounts record a payment of £1,000 by Joseph Andrews on 20th October 1758 to insure Shaw Place, Berkshire.

One main alteration in the 19th century dramatically changed the character of the Hall and the rooms over it. The construction of an open loggia and panelled corridor across the north side of the central range allowed access to different areas of the house without passing through rooms. These additions blended in with the original exterior of the house; however the loss of light and views over the gardens

8 Huntington Library, Stowe correspondence. ST57, Vol 33, 1728/9-29.p. 245 5th September 1729

9 Huntington Library, Stowe correspondence, ST57, Vol. 34 1729-30, 9th Dec p. 40

10 West Berkshire Museum, Joseph Andrews Notebook 1750. D/ENm1/F14

from the large north facing windows altered the experience of the interior. Also in this period, the exterior of the house was restored to its 16th century appearance by the reinstatement of the mullion windows. The later owner of Shaw, Mrs Farquhar, inserted the smaller rectangular panes of glass within the mullion windows that can be seen today.

Shaw Under Siege

An account of the parsonage at Shaw being burnt down in February 1643 is the first indication of the Civil War effecting Shaw.

“About eleven o’clock in the night, Mr John Royston parson of

Shaw had all his dwelling house, stables, outhouses, books, plate,

Money……..utterly burnt consumed to ashes, not by any neglect of

his, or any other known cause”11

Throughout the Civil War, Newbury’s location on the route from London to the West Country made it strategically important. Donnington Castle, a mile to the north-west of Shaw remained a Royalist stronghold. By October 1644 Royalist fortunes in the area had waned and Charles I returned from the West Country to relieve the besieged garrison at Donnington castle. Shaw House had become an integral part of the Royalist defensive position. By 26th October a large Parliamentarian army was gathered at Thatcham to the east of Shaw. The Royalist forces were greatly outnumbered but they had the advantage of a strong defensive position. The river and marshy ground to the south of Shaw together with the raised terraces around the garden made Shaw House the ideal place for the King to have his headquarters for the ensuing battle. Tradition has it that the King narrowly missed being hit by a musket ball as he dressed on the morning of the battle. To this day a brass plaque marks the place where the panelling in the first floor south-east room was damaged by the shot. It states that the hole in the panelling “was occasioned by a ball discharged from the musket of a Parliamentary soldier at King Charles the first”

11 BRO D/EX17/1 Z2

In the middle of the afternoon of Sunday 27th October the attack from the west of Shaw began. Fortunately for the Royalists another attack from the east started at least an hour too late to take full advantage of the initial confusion caused by the attack on the west. The strong positions of the Royalist infantry behind the raised garden terraces enabled them to fire in safety on the approaching psalm-singing Roundheads. The fighting was fierce with many casualties on both sides and fighting reached the immediate vicinity of the house; the walls still bear the marks of musket shot. Skeletons found in the grounds (both human and equine) suggest that some casualties were buried where they fell or were blown to pieces by cannon shot. The tradition of the rousing battle cry of “King and law shouts Dolman of Shaw” suggests that Thomas Dolman was in the thick of the battle.

What is certain is that the raised terraces that surrounding the garden at Shaw were a significant factor in the Royalists being able to hold their position and the Parliamentarian abandoning the day.

On the north side of this highway a strong House belonging to

one Mr Doleman, having a Rampart of Earth about it,”12

“the greatest part of the Army was placed towards the Enemies Quarters

in a good House belonging to Mr Doleman at Shaw …..about which a

Work was cast up”13

Despite the Royalists successful defence of Shaw their position was unsustainable and undercover of darkness they retreated; the King to Bath and his commanders with their soldiers and guns to the relative safety of Donnington Castle. To the Parliamentarians this was an unsatisfactory end to the battle; their tactics had failed largely due to bad leadership and they had let the King slip away from their grasp.

12 Ludlow’s Memoirs, 1696

13 Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England, Volume II Book 7, 1703

Discover Shaw: The Ground Floor

The house follows a typical arrangement for houses of this type during the late 16th century, the ground floor rooms being organised around the Hall in the central range. This was separated from service areas to the west by a screened passage. To the west of the screen a paved corridor led to the kitchen and service area, with the west external door leading to the stable yards and manor farm.

The house follows a typical arrangement for houses of this type during the late 16th century, the ground floor rooms being organised around the Hall in the central range. This was separated from service areas to the west by a screened passage. To the west of the screen a paved corridor led to the kitchen and service area, with the west external door leading to the stable yards and manor farm.

The Hall was originally lit by windows set high in the walls on both the north and south sides; it is now hard to imagine the effect of light pouring into the hall from windows on both sides of the room. The sills of the two windows lighting the main body of the hall were originally much lower than today. The Elizabethan fireplace was positioned between the north facing windows which were blocked in the 19th century when the loggia was installed. The high status end of the Hall at the east had a raised dais from which a doorway positioned at the north end of the wall led to the foot of the original staircase, remains of which were discovered during the restoration of the house. The hinges for a dog gate also remain in the door frame at this end of the Hall leading to the private apartments. Dog gates were used to prevent the household dogs, which had free access to the public parts of the house, from coming into the family’s private rooms. This is a reminder of the nature of life in large houses such as Shaw at this time where the commotion of the household would have spread from the yards to the west of the house, into the service rooms and on into the Hall.

The east stair that we use today was constructed towards the end of the 17th century, incorporating details that are very similar to work carried out at Kensington Palace and Hampton Court in the 1690s. Sir Thomas Dolman’s position at Court would have made him aware of the latest trends in architecture and even enabled him to employ craftsman who had worked on these commissions. Also at this time, the hall was reorganised to create an appropriate approach to the new staircase and was panelled to match the other principal rooms. The screens passage was removed and the low 16th century doorways were blocked, concealed or enlarged. The dais was removed and a flight of stone steps put in place, leading to a large door. The sills of the hall windows were lowered; this alteration also let more light into the room and made it possible to look out to the gardens and forecourt.

On the ground floor of the east wing the rooms that can be identified from the 1622 Inventory are the study at the north end (the Ceremony Room today) and the parlour overlooking the forecourt to the south (now Chandos Dining Room). These spacious private apartments with high ceilings, large fireplaces and windows provided the kind of accommodation essential for comfortable living and entertaining. These features would have been apparent from the outside; the clusters of tall chimneys indicated numerous fireplaces and the large windows suggested well proportioned rooms. The fine 16th century fireplace in the Chandos Dining Room is similar to those in houses built at the same time as Shaw and it may therefore be one of the few original fittings remaining in the house.

The Chandos Dining Room takes its name today from its use in the 18th century by the Duke. His Dining Room would have held ‘Indian Papers’ hung in specially prepared panels made to fit, possibly the originals of the ones now in place (see The Decorative Scheme). The Duke of Chandos also installed a narrow service stair between this room and the staircase hall, providing access to every floor from the cellar to the attics. The passage in the basement connecting the two wings of the house made it possible for food to be brought directly to the dining room from the kitchens through the cellars.

The Kitchen (now the Café) has retained its position occupying the whole of the north of the west wing. It was originally lit by high windows on three sides but only the west windows remain in their original form. The inward facing east window was blocked by the water closet tower built for the Duke of Chandos in 1730 and the sill of the window in the north wall was raised to accommodate the late 20th century external door. The original massive 16th century kitchen fireplace with a four centred arch of chamfered brick remains. In the Victorian period the kitchen and service areas were modernised to bring the facilities up to date and an extension was developed to the north of the kitchen to provide a new service range. The contemporary smoke jack manufactured by Jeakes & Co remains in the former kitchen to indicate the quality of the equipment installed. During the time of Mrs Farquhar’s ownership, the Victorian extension to the kitchen was lengthened to accommodate a new servants’ hall, and bedrooms for male servants as well as a game larder and lavatories. These extensions were later partially demolished during developments for Shaw House School in the 1960s. More will be revealed about the kitchen in a later chapter in this book, ‘Archaeological Investigations’, which looks at the secret that lies beneath the Café …..

The suite of rooms at the south end of the west wing is entered through the 16th century doorway. The position of the doors leading into the Oak Room and its closet were revealed during restoration when the Jacobean panelling was removed from the walls. Despite its position in the servant’s wing of the house these rooms are of a high quality suggesting higher status than other rooms to the west of the hall. One theory for this oddity is that in the last years of Thomas Dolman’s life, he used this as his bedroom. This is implied by the Inventory taken of Shaw in 1622. With its view across the main drive and convenient location on the ground floor, it may have provided an ideal chamber for the elderly gentlemen.

A Dukes Country Retreat

The Duke of Chandos finally gained possession of Shaw House14 on March 25th 1728 having agreed to pay £28,441 (the equivalent of approximately £3m in 200515). It was two and a half years before the house was ready for occupation. In September 1730 Cassandra, Duchess of Chandos wrote to her cousin from Shaw: “I was in such a hurry making provision for our journey to Shaw House, I was not able to write ….we have not been long enough at Shaw House for me to be at rest from the work necessary to be done upon first coming to an empty house, but when better settled, tis a place which I believe I shall be very much pleased with…”16

The Duke of Chandos finally gained possession of Shaw House14 on March 25th 1728 having agreed to pay £28,441 (the equivalent of approximately £3m in 200515). It was two and a half years before the house was ready for occupation. In September 1730 Cassandra, Duchess of Chandos wrote to her cousin from Shaw: “I was in such a hurry making provision for our journey to Shaw House, I was not able to write ….we have not been long enough at Shaw House for me to be at rest from the work necessary to be done upon first coming to an empty house, but when better settled, tis a place which I believe I shall be very much pleased with…”16

James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos was a member of an aristocratic family that owned estates across the country. |He was appointed Paymaster General of the Queen’s forces abroad in 1707. The precise reasons for buying Shaw will never be known but it was to become the Duke and Duchess’ private country retreat from their busy public life in London and their home there, Cannons. It is possible that they simply wanted a conveniently located country house mid-way between London and Bath, where they could enjoy the company of their close friends and family. Additionally Chandos was optimistic about making money from peat deposits near the river Lambourn and from the sale of timber on the estate.

Chandos employed the surveyor William Godson to survey the estate in the winter of 1729. The resulting estate map, known as the Map of Speen,17 survives to provide a detailed image of Shaw at this time. A survey of the buildings made by the local mason Jonathon Hicks established that the roof and the old-fashioned mullion windows leaked, masonry needed repairing and cleaning, and the plumbing was out of date. Chandos’ extensive correspondence with his agent Mr Hall, and his long-suffering steward Mr Fergusson, gives a detailed and at times entertaining picture of life at Shaw during these years. It appears that the existing bailiff had been neglecting his duties, as the Duke described the gardener as being “good for nothing18….no body could indeed perceive that he had done anything at all besides gathering the fruit off the trees a fast as it grew ripe”19. He employed Edward Shepherd, the architect who had worked on his London house, to undertake the decoration of a new dining room but Chandos soon complained that Shepherd’s workmen were producing work of “supine negligence” and were even on occasion “scandalously drunk from morning to night”20!

14 Shaw House also referred to as Shaw Hall when it was owned by Chandos

16 Cassandra, Duchess of Chandos, Letterbook Letter 304 North London Collegiate School

17 On display at West Berkshire Museum, Newbury. Ref NEBYM:1991.73

18 Huntington library, Stowe correspondence ST57, Vol. 33, 1728/9-29.p.310 6th November 1729

19 Huntington library, Stowe correspondence ST57, Vol 33, 1728/9-29.p.352 25th November 1729

20 Baker & Baker, The Life and Circumstances of James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos. P. 370

Chandos’ most spectacular contribution to 18th century Shaw was an elaborate water garden to the south of the house. In March 1733 he employed the canal engineer John Hore to create a single broad canal from the narrow twin canals made only thirty years before and dig a semicircular basin out of the north bank of the river into which a cascade flowed from the canal. The south front of the house was then reflected in the semi-circular basin. The death of Cassandra in 1735 and the Duke’s subsequent marriage to Lydia Davall in 1736 marked the end of his regular visits to Shaw. The house was let to his son the Earl of Carnarvon until 1743. The following year the Duke died and his widow moved to Shaw, where she lived for the rest of her life. Shortly before her death in November 1750 she negotiated the sale of the estate on behalf of the 2nd Duke of Chandos to Joseph Andrews.

Discover Shaw: The First Floor

One unique aspect of Shaw House is the design of four symmetrical suites of rooms based at each end of the wings on the first floor. Each suite consisted of a large chamber with a closet accessed by a corridor and lobby. The chambers are still lit today by large windows looking over the grounds; like the floor below the inward facing walls are taken up with large chimney stacks. The suites of rooms in the west wing have been less affected by alterations and their original sequence can be established from the position of the blocked doors.

The central range of the first floor was redeveloped towards the end of the seventeenth century. Three large rooms were designed here as a state apartment which was approached from the impressive east staircase. Their doorways are on the south end of the rooms in line or enfilade with a mirror positioned to the very west of the line to create the illusion of length. Uniform ‘bolection-moulded’ panelling was put up in the newly refurbished rooms and small stone moulded fireplaces replaced the originals. From the windows of these rooms there would have been spectacular views to the south of the new water gardens with their narrow twin canals reaching into the distance. An Orangery built across the end of the north facing garden framed the view from the windows on the north side of these rooms.

Years later, in 1907 the north-east room on the first floor was panelled with Jacobean panelling that had been stored in the attics and became known as Queen Anne’s Bedroom. The names of the workmen who did this work are known from an inscription on the plaster close to the cornice. According to the Country Life article about Shaw House at this time the drawing room over the hall also had a new fireplace which had been “secured because of its charm” by Mrs Farquhar.

Not to be missed on the first floor of Shaw House is the evidence of Shaw’s most infamous tale – the plaque marking the location where King Charles I was almost shot. The full story is recounted earlier in this book in Shaw Under Siege.

A Georgian Country Estate

Like the Duke of Chandos, Andrews planned to modernise the house and make further changes to the grounds. His death within two years of completing the purchase meant that many of his ideas were never realised. A group portrait of the Andrews family painted the year before the purchase of Shaw depicts them as a wealthy family displaying all the symbols of social success.21 By the time Joseph Andrews bought Shaw he was a very wealthy man deriving a substantial income from extensive properties in London, as well as having a financial stake in sugar plantations in Jamaica and Dominica.

Notebooks

Joseph Andrews was a habitual record keeper and his Notebooks22 provide a remarkable record into the spending habits of a wealthy gentlemen at this time. He carefully noted his daily expenses that ranged from the cost of tolls for turnpike roads and the repair of clothing, to bills run up in coffee houses and pocket money for his children. In 1751 Andrews made measured drawings for the improvements he intended to undertake at Shaw. He completed a tree-lined drive in the grounds leading from Bath road to the house crossing the river Lambourn by a new bridge. Andrews also made detailed records of Chandos’ water features, as well as the position and ground plan of the original church which was to be demolished in 1841. On his death in April 1753 Joseph Andrews was buried at Hampstead in London.

A Social Reformer at Shaw

Joseph Andrews’ elder son, also Joseph, was twenty-six when he inherited the estate. On 19th August 1766 Joseph Andrews was created 1st baronet Andrews of Shaw, an honour that was said to have been procured “by paying a voluntary subsidy in aid of the King’s measures against the turbulent proceedings in Ireland.”23 Contemporary accounts suggest that George III and Queen Charlotte were entertained by Sir Joseph at Shaw House24. He continued his father’s habit of keeping a record of his accounts and personal recollections in a notebook25. There are many entries within these for donations to the poor of the parish and also to London Hospitals. His commitment to improving the conditions of the poor was demonstrated in his part in the Speenhamland Act that was instituted in the Pelican Inn, Speen on May 6th 1795. This was a local scheme that aimed to reduce the hardship of the poor by linking the poor rate to the cost of a gallon loaf of bread. He was also involved in the campaign to improve conditions for chimney sweeps at this time. Despite being married twice he had no surviving children and following his death at the age of seventy-three in December 1800, the Manor of Shaw and the title passed to his nephew Joseph, the son of his half-brother James Pettit Andrews.

21 James Wills, The Andrews Family s&d 1749. Sitters identified as Joseph Andrews, his 2nd Wife Elizabeth, their son James Pettit Andrews, his elder son Joseph (by his 1st Wife) and an unidentified woman who may be Miss Andrews, his sister. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

22 West Berkshire Museum BRO D/ENm1/F14

23 Michael Macleod, Shaw House Unmask’d 1999 page 144

24 Mrs Papendick, Court and Private Life in the Time of Queen Charlotte, 1790

25 BRO D/ENm1. (1766-99)

The Last of the Andrews Family

Joseph Andrews was thirty-two when he inherited Shaw Place as it was known at this time. A bachelor, he had followed a military career from the age of sixteen. Sir Joseph never married and following his death in February 1822 the estate passed to his sister Elizabeth Anne who was married to Charles Hunt. She died childless within five months of her brother’s death. A small engraving of the east front of the house made by Elizabeth Hunt before the death of her brother26 provides evidence of Chandos’ sash windows. The central sash window in the south east room opened to floor level with a sloping ramp allowing direct access to the gardens. The earlier formal gardens have been replaced by groves of tall conifers framing the view of the house. Under the terms of Sir Joseph’s will, following the death of his sister without a direct heir, the estate passed to his cousin, the Rev Dr. Thomas Penrose, the son of his mother’s brother.

A Victorian Family Home

Henry Richard Eyre the grandson of Sir Joseph Andrew’s aunt was born in Perth, Scotland. The first documentary evidence of him living at Shaw is stated in the 1847 Kelly’s post Office Directory27. By 1851 he was sufficiently established in the vicinity to be appointed a Justice of the Peace, the year he inherited the estate. Henry Eyre married Isabella Parker in 1849; their six children born between 1853 and 1860 were the first to be raised at Shaw in over a century. Census returns in 1861 and 1871 provide a record of those living at Shaw during this period 28; in 1861 five of the eleven servants in the house were engaged solely in the care of the children29. The arrival of the Eyre family at Shaw signalled a period of dynamic change. The majority of the improvements were driven by the need to bring the house up to date and make a comfortable family home for their ever growing family. The house was extended to improve access to different parts of the house and modernise the service areas. Henry Eyre died in May 1876 at the age of sixty-three after a short illness whilst staying in Brighton30. The estate had been settled on his wife Isabella for life at the time of their marriage and she continued to live at Shaw with her children until 1882.

In June 1888 the house was put up for auction; the sale catalouge31 provides a detailed account of the estate at this time. The house failed to reach its reserve of £60,000 and Mrs Eyre returned to live there until at least 1891. Later that year she left Shaw for the last time. During her final years Mrs Eyre lived in the village of Merrow near Guildford with her unmarried daughters, Isabella and Mabel. Merrow is little more than six miles from Polesden Lacey, the country estate of the Farquhar family and it is highly likely the two families would have been acquaintances. Mrs Eyre died aged eighty-four in May 1904.

On 3rd August 1905 the Newbury Weekly News announced the sale of Shaw House to Mrs Eyre’s neighbour, the Hon Mrs. Kathleen Farquhar. Before Mrs Farquhar moved into her new home the contents of the house were sold. In September 1905 Hampton’s conducted an initial sale at Shaw House; however the more valuable items were reserved for a sale held at Christies in early December.

26 NEBYM:D3168

27 The 1841 Census record both Henry Eyre and Thomas Penrose staying at an address in Canterbury

29 Governess, Nurse, Wet Nurse, Second Nurse and Nursery Nurse

28 Isabella is incorrectly given the age of 62 in the 1871 census

30 Report in the Newbury Weekly News, June 1st 1876

31 NMR Swindon

The Twentieth Century

Kathleen Farquhar was the youngest daughter of Thomas, 1st Lord Deramore of Co. Down. In 1877 she married Walter Randolph Farquhar. Kathleen and Walter’s only child, also Walter, was born in May 1878. Mrs Farquhar’s husband died in 1901. Soon after Mrs Farquhar moved to Shaw she began a major programme of renovation, much of which still remains a century later. The work of her architect, a Mr Fielding, did much to preserve the original character of the house. At the same time as the structural alterations, modern conveniences were incorporated including the installation of electricity throughout the house. Many of the changes can be detected from two sets of photographs taken of the house by Country Life magazine in 1906 and 1910. Mrs Farquhar brought some items to Shaw when she moved in, but as a keen collector of antiques both in England and France32 she bought much of the furniture to fit in with her new surroundings.

Community Disputes……

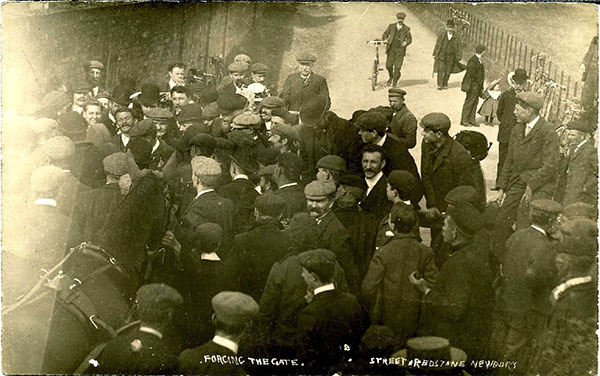

In 1907 a dispute over the public right of way along Church Road led to a major confrontation with local people. On Good Friday 1907 a crowd of parishioners finding the road to the church barred by a locked gate broke it down in an act of defiance. Mrs Farquhar intended to establish the road as a private gated drive along which public access was at her discretion. She was upset by the increasing numbers of traction engines and other vehicles which disturbed the otherwise peaceful environment. The case went to the High Court in July 1908; numerous local people were called to give evidence of how the road had traditionally been used. In the event, despite taking the case to the Court of Appeal, Mrs Farquhar lost the case and the right of free public access was established. As a result Mrs Farquhar had a wall built with high railings and central gates put up to enclose the forecourt. A new drive leading from the gates to the front door was laid out and the old drive became a gravel path to a pedestrian gate in the new boundary wall.

In 1907 a dispute over the public right of way along Church Road led to a major confrontation with local people. On Good Friday 1907 a crowd of parishioners finding the road to the church barred by a locked gate broke it down in an act of defiance. Mrs Farquhar intended to establish the road as a private gated drive along which public access was at her discretion. She was upset by the increasing numbers of traction engines and other vehicles which disturbed the otherwise peaceful environment. The case went to the High Court in July 1908; numerous local people were called to give evidence of how the road had traditionally been used. In the event, despite taking the case to the Court of Appeal, Mrs Farquhar lost the case and the right of free public access was established. As a result Mrs Farquhar had a wall built with high railings and central gates put up to enclose the forecourt. A new drive leading from the gates to the front door was laid out and the old drive became a gravel path to a pedestrian gate in the new boundary wall.

32 Recollection of Ruth, Lady Dulverton

Life at Shaw House between the Wars

On October 15th 1918 captain Sir Walter Farquhar, 5th Bt. Was killed in action whilst serving in the Royal Field Artillery (59th Division). There is a memorial to him in the south wall of the chancel in Shaw church. After Sir Walter’s death, his widow Lady Violet Farquhar33 and their four children came to live at Shaw. Mrs Farquhar’s elegant country house was reorganised to accommodate her grandchildren – once more Shaw had a young family under its roof. Her granddaughter Ruth’s recollections34 of Shaw during this time, bring it to life.

The children’s rooms were on the second floor. The three boys, Peter, Charles and Reginald shared a room but their sister Ruth had a room of her own close to the nursery. There was a governess and an under-governess to teach the children, both of whom had rooms close to the children’s. When they were old enough the boys were sent to boarding school but Ruth was educated at home.

A Butler called Margison was the only male servant who lived in the main part of the house; his room was to the left of the front door. All the other male servants had rooms either in the service range to the north of the kitchen or in the stable yard. The housekeeper, Mrs Cotton, had a large sitting room next to the Butler’s room. There were eleven other female servants employed in the house all of whom slept in rooms on the second floor of the west wing, separated from the children’s room by a red baize door. At meal times all the servants ate the main course together in the Servants Hall; after this the more important servants followed Margison and Mrs Cotton in procession to the housekeepers’ sitting room where they ate their pudding. The Head Gardener at this time was Mr Saunders. He is photographed wearing his bowler hat, standing in the formal rose garden to the north of the house in one of the Country Life photographs. The gardens were looked after by a further five gardeners, one of whom was responsible for mowing the lawns using a lawnmower pulled buy a horse called Mick, who wore leather boots to prevent his hooves damaging the lawns. Amongst many pet animals a particular favourite was a Donkey which frequently escaped and roamed free across the gardens, much to the consternation of the children’s grandmother.

After Mrs Farquhar’s death in July 1935, her grandson Sir Peter Farquhar, 6th Bt. inherited the estate. Sir Peter married Elizabeth Hurt in 1937. Their eldest son, Michael was born in June 1938 and for little more than a year Shaw House remained their family home. At the outbreak of the Second World War in August 1939 the house was requisitioned for the army.

33 Violet Maud Corkran. Married Sir Walter Farquhar on 17th December 1903

34 Ruth, lady Dulverton, daughter of Sir Walter Randolph Farquhar. 5th BT. Grand-daughter of Kathleen Farquhar

The Second World War

Within weeks of the start of the War Shaw was transformed for use by the army. Air raid shelters were dug in the rose garden to the north of the house and a lavatory block was built to the east of the forecourt. The grounds became a military training area, initially for men from the Royal Army ordnance Corps before they were transported to France in December 1939. In 1942 Shaw became the base for the Air landing Reconnaissance Squadron, which in 1944 was to take part in the Arnhem campaign. The house accommodated over two hundred men – a far cry from the pampered households of the earlier times. Later in 1942 American and Canadian troops were housed at Shaw; these troops were subsequently to take part in the D-Day landings on the beaches of Normandy in 1944.

Within weeks of the start of the War Shaw was transformed for use by the army. Air raid shelters were dug in the rose garden to the north of the house and a lavatory block was built to the east of the forecourt. The grounds became a military training area, initially for men from the Royal Army ordnance Corps before they were transported to France in December 1939. In 1942 Shaw became the base for the Air landing Reconnaissance Squadron, which in 1944 was to take part in the Arnhem campaign. The house accommodated over two hundred men – a far cry from the pampered households of the earlier times. Later in 1942 American and Canadian troops were housed at Shaw; these troops were subsequently to take part in the D-Day landings on the beaches of Normandy in 1944.

One enduring story from Shaw’s war years demonstrates the antics that occurred when Sir Peter Farquhar let the Americans of Company B 205th QMBM (GS) loose in his house…..

“Exploration led the men to the wine cellar, hugely stocked with precious wines, champagnes, cognac and other goodies. They were soon able to open the stout iron door and begin to help themselves to the wine with drastic results. It was some weeks before the deed was discovered.” (Lieutenant Martin W Parcel)

Troops continued to be accommodated at Shaw until February 1943. In May of the same year the house became temporary school accommodation after the bombing of the Senior Council Schools in Newbury on 10th February 1943. In 1945 following the end of the War Sir Peter Farquhar could see no future for Shaw as a home for his growing family and consequently he put the estate up for sale. The sale on 20th June 1945 ended in confusion with the house unsold. A week later it was sold to Gabriel’s School but the council retained the property for the Council School. Ion 1949 it was finally purchased for £13,000 by Berkshire County Council to ensure its continued use by the Council School and to allow the development of improved facilities on site.

Shaw House School

Over the next forty years, the school evolved in line with developments in education. It became clear very quickly that Shaw House was not large enough to accommodate both the boys and girls departments. So from 1947, the boys gradually moved to the new Park House School, making Shaw House girls-only by 1956. In 1979, the school became co-educational once more. All past pupils and teachers will agree that they thoroughly enjoyed the very special privilege of education in a very unique setting.

The provision of permanent sports facilities for the school across the grounds started in 1958 with the construction of a gym adjacent to Love Lane to be joined by the new swimming pool which was opened by Mrs Parker Bowles of Donnington Castle House on 21st June 1961. Much needed additional teaching space was provided in 1963 by the construction of the Astley Building immediately to the west of the house, on the site of the old stable yard and the Victorian Wilderness Garden. Tarmac tennis courts were laid out in the Great Garden and in the north east of the former Kitchen Garden. A new sports hall was built in the early 1980s to the east of the Great Garden.

At the same time as the alterations to the house and its grounds were being made by the school, the area around it was being encroached upon by housing. At about the same time the canal finally became silted up and it appears to have been filled in during the 1960s. Further incursions into this area were made in the 1970s with the expansion of the network of roads linking the M4 and Newbury. In 1985 Shaw House’s time as a school building was ended abruptly by the discovery of serious structural defects which led to the immediate evacuation of the school.

Discover Shaw: The Second Floor

The high quality oak flooring and large three-light windows on the second floor suggest it was always used as a living space, rather than an empty attic. The 1622 Inventory mentions a gallery at the east end which fits in well with other contemporary high level galleries in large country houses. These were used for several purposes; entertaining guests, displaying art, and places for exercise in bad weather.

In the nineteenth century when Shaw housed the Eyre family, the attic floor was converted to provide accommodation for the children as well as servants’ rooms. A door at the west of the central range with red baize on the far side of it marked a clear division between family and servants. To the east of this door were the children’s bedrooms, nurseries and a school room. Contemporary engravings and early photographs show dormer windows of this period necessary to light the attic rooms as well as a chimney for the newly installed fireplaces.

The attic floor was reorganised once again in the twentieth century to provide more accommodation for female servants and after 1918, rooms for Mrs Farquhar’s grandchildren and their governesses. As part of this work the roof was re-roofed, new dormer windows inserted and additional chimneys were built for new fireplaces.

The Decorative Scheme

There is very little remaining evidence of the original interior decoration of Shaw House. Due to the Dolmans involvement in the cloth industry, it is likely that some of the walls were covered by textiles. However the Inventory of 1622 gives no indication of the wall hangings that might be expected, so this remains uncertain.

There is very little remaining evidence of the original interior decoration of Shaw House. Due to the Dolmans involvement in the cloth industry, it is likely that some of the walls were covered by textiles. However the Inventory of 1622 gives no indication of the wall hangings that might be expected, so this remains uncertain.

Some of the decorative changes made by the Duke of Chandos survive in the south-east of the ground floor where he had a new dining room and service stair constructed. Stucco panelling with egg and dart moulding was made in order to frame a series of what Chandos referred to as Indian pictures. In April 1730 he wrote to his architect Edward Shepherd with the following instructions: “As we have several Indian pictures, I would have the sides of the Room he is altering intended for the Dining Room, to be worked out into stucco panels, so that they may fit each Picture”35 .By June Chandos had decided to have the Dining Room painted and gilded as well, but this work was delayed until the following year.

The stucco ‘frames’ remain as a reminder of the grandeur of the interiors at Shaw in the 18th century. Paint analysis here has revealed that the walls were painted q warm off-white colour. Although fibres of the Indian paper have been found in the room, there is no further reference to the pictures and it seems likely that they were removed before the house was let in the 1740s. Today, striking, high quality digital photographs of similar papers can be seen in the Chandos Dining Room, an attempt to recreate its former decorative style. The papers were reproduced from originals currently hanging at carton House in Ireland.

In the latter half of the 18th century, during the period the Andrews family owned Shaw, it is likely that there would have been many changes to the interior decoration of the house reflecting the fashions of the time. The only surviving evidence is in a small room on the first floor of the west wing where the panelling was removed and canvas stretched to provide a smooth surface on which wallpaper could be hung. Fragments of block printed architectural or ‘Pillar and Arch’ paper with blue verditer background dating from c. 1755 have been found here. Usually on a grey background, the only other known example of a similar blue paper is at Springhill in Northern Ireland. One wall of this was discovered, with reproductions completing the scheme.

It has also been found that the Eyre family completed some redecorations of their own just after they moved into Shaw in the 1850s. The surviving evidence for this is a handwritten inscription on one of the glass window panes above the east staircase, upon which the workmen left their mark. “This staircase, Hall, Morning and Breakfast Rooms painted 1856. W. Balding, C Griffin, H Toomery, G Eyres, H Colling for W G Boyer, Newbury.”

35 Huntington Library, Stowe correspondence. ST 57, vol.34, 1729-30.p.263 4th April 1730